Brownian Motion

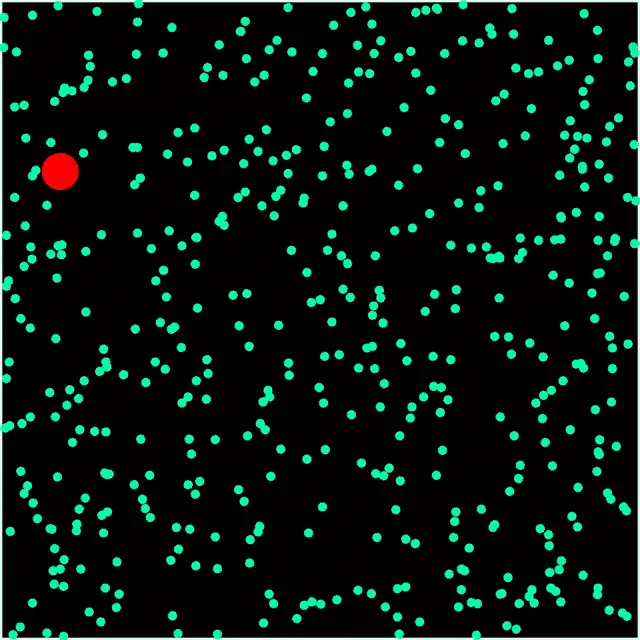

In this blog, I am going to explain about one of the simple yet complex phenomena - Brownian motion, and why it is important. The random motion of a small particle (about one micron in diameter) immersed in a fluid with the same density as the particle is called Brownian motion. The history of Brownian motion starts with the botanist Robert Brown, who first observed this motion in grains of pollen. Later, Albert Einstein reasoned that if tiny but visible particles were suspended in a liquid, the invisible atoms in the liquid would bombard the suspended particles and cause them to jiggle. He explained the motion in detail, accurately predicting the irregular, random motions of the particles, which could be directly observed under a microscope. Paul Langevin later proposed a different approch to prove Einstein's theory.

Langevin Equation

The fudamental equation for Brownian motion is called Langevin equation. Consider a large particle immersed in a fluid of much smaller particles. For simplicity, we are going to consider one dimension. But the results are easily generalisable to three dimensions. From Newton's equation of motion, we have, $$ m \frac{d^2 x}{dt^2} = F(t) $$ Where $F(t)$ is the total instantaneous force on the Brownian particle at time $t$. If we know the exact position and velocity of all the molecules present in the surrounding medium, then this force is exactly known. But it is not practical to look for the exact form of $F(t)$. One idea is that to split $F(t)$ into two components. One is a frictional force $-\gamma v$, which is proportional to the velocity of particle (Stokes' friction). The another part is a random force $\eta(t)$ due to the fluctuations in the fluid. Thus, the equation of motion becomes, $$ m \frac{d^2 x}{dt^2} = -\gamma v(t) + \eta(t) $$ This is the celebrated Langevin equation of motion for the Brownian particle. Now, let's talk about the term $\eta(t)$. If we neglect $\eta(t)$ from above equation, we get $$ m \frac{d^2 x}{dt^2} = -\gamma v(t), $$ which has the familiar solution $$ v(t) = v(0) e^{-\frac{\gamma}{m} t} $$ Hence, the average kinetic energy of the particle (averaged over the ensemble) is, $$ K = \frac{1}{2} m \langle v^2(t) \rangle = \frac{1}{2} m \langle v^2(0) \rangle e^{-\frac{2\gamma}{m} t}. $$ This will be zero in the equilibrium case due to the exponentially decaying term. However, the equipartitian theorem says that at equilibrium, particle will have kinetic energy of $\frac{1}{2} k_B T$. Thus, the random force $\eta(t)$ is therefore necessary to obtain correct equilibrium condition.